Mixed. Peach. Black.

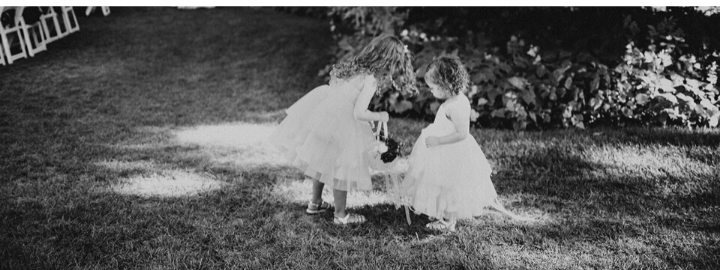

My wife is dancing playfully with our two girls—ages two and four. “Show me that Black girl magic,” she says, and the girls twirl and jump excitedly. This is a normal day in the life of the Nightingale household, even though the skin tone of the kids looks a lot like daddy’s.

The importance of our girls understanding their identities is reflected throughout our daily choices. Dolls are different shades. Our first book was A is for Activist by Innosanto Nagara. In another favorite, Shades of Black: A Celebration of Our Children by Sandra L. Pinkney, Black children span from “the creamy white frost in vanilla ice cream” to “milky smooth brown in a chocolate bar” and many other shades. Our four-year-old has decided that she is peach. With Black girl magic. And a white daddy. It’s a little confusing.

And now we have a son—a future Black man in America, but one that will undoubtedly benefit from white privilege. Or at least peach privilege.

Our kids are “mixed.” But in a one-drop-rule world, a Jim Crow era classification to count anyone with a single drop of African blood as Black, they are Black. And as teenagers, if they are stopped by the police at night, they will likely be perceived as white. It is heartbreaking how comforting this fact is to me with their safety as my only priority.

When my wife and I decided to move from the city to Westchester to start our family, we weighed the best public schools our property taxes could afford versus diversity. The American reality, the legacy of constant segregation and exclusion, is that it is one or the other. African American families have less wealth (an appalling 10 times less according to CNN’s recent article “US black-white inequality in 6 stark charts”), rarely start life with generational inheritance, and are disproportionately in poorer communities with under-resourced school systems. Cue generational cycles of poverty. Cue white flight. Cue the deeply segregated world we currently live in.

Like many parents would, we chose the best schools possible, and it’s on us to teach our peach girls all about their Black girl magic. But this false choice is tragic.

It is a good thing that some police captains are choosing to kneel with protestors this week. But are police departments willing to hire and promote differently to become reflective of the communities they serve? Are they willing to break the blue shield and diligently root out the “bad apples”? It is nice to see #blacklivesmatter on my social media feed. But are we collectively willing to put real systems in place to redistribute wealth and opportunity? Are we ready for tomorrow to look fundamentally different than today?

At the core of the racial divide in America is the most basic human weaknesses. Fear of what we are not. Fear that you getting more means me getting less. And for white people, it is time to face the realities of white fragility. That the way things are isn’t the way they should be. That we don’t inherently deserve the things we have. That far too many of us started life on third base and act like we hit a triple.

It can be argued that overall the plight of African Americans has slowly (way too slowly) and steadily improved. Some African American families have ascended into the middle and upper classes and changed the trajectory of their generational path.

But the flagrance of the very idea of racism—the audacity to hate and degrade on the basis of skin color—has not changed at all. Its flagrance persists with tragic consequences.

One day I’m going to have to explain this all to my kids. Daddy’s privilege. Mommy’s overflowing well of Black girl magic. How great their mixed, Black, peach-ness makes them. But for now, they are having too much fun dancing with their mommy. And our world is far too embarrassing to introduce to their sunshine.